It has been a while since the last installment in the Gregorian Chant Notation tutorial series. I’d like to pick up again with the next topic: Neums and Why They Matter. If you missed either of the earlier articles in the series, now would be a good time to review them:

- Part 1 – Gregorian Chant Notation: Getting Started

- Part 2 – Gregorian Chant Notation: Solfege

Neums

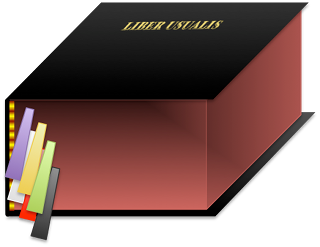

Before diving in, let us briefly review what a neum is. A neum is a set of one or more notes sung on the same syllable. Sometimes, multiple neums are strung together on the same syllable to build a compound neum, but generally speaking, a simple neum is composed of between one and four notes. The following page from the Liber Usualis identifies the simple neums as well as a few compound neums.

Of these, the most important ones to know in practice are the following:

- Punctum – a single, square note

- Virga – a single, note with tail

- Podatus – two ascending puncta

- Clivis – two descending notes

- Scandicus (and its close relative the Salicus) – three (or more) ascending notes

- Climacus – three (or more) descending notes

- Torculus – three notes, the second higher than the other two

- Porrectus – three notes, the second lower than the other two

- Strophicus – two or three notes on the same pitch (2-note is called “distropha”; 3-note is called (“tristropha”).

It can be good to know the names of the following, although, in my own experience, I haven’t needed to know their names as frequently:

- Bivirga – the distropha-equivalent for the virga

- Epiphonus – two notes with liquescent above the first note

- Cephalicus – two notes with liquescent below the first note

- Pressus – looks like a strophicus mashed into a clivis

Many of the other neums presented on this page are combinations of other neums or variations on another neum, for example, the Porrectus Flexus.

To avoid confusion, the quilisma, which is shown above, is not itself a neum but is the squiggly looking note that appears in other neums, but never by itself. Also note, the discussion on the page about the podatus. As is the case with all of the neums, the actual number of lines or spaces between notes is variable, provided the pattern remains the same. Thus, the three examples given (fa-sol, re-la, sol-do (ut)) are all valid examples of the podatus.

Why Neums Matter

It can be tempting to conclude that, with a thorough and practiced understanding of solfege, one does not really need to learn the neums. They all have Latin names that don’t mean a whole lot to our English ear, and we can sing through them mechanically from left to right and bottom to top. This works to a point, but I think this reasoning is ultimately incorrect.

The neums have their own characteristics of emphasis and dynamic contrast, and understanding these helps us sing with greater feeling. Practically speaking, knowing the names of the neums also helps when practicing in a group. Rather than saying, “Watch for the third note of the syllable ‘ce’ of ‘Ecce’…” one can instead say “Watch out for that torculus in ‘Ecce’…” Everyone then knows you are talking about a note construct that looks like this: ![]()

Interpretation and Dynamic Contrast

In general, the second note of a neum is sung softer than the first. There are exceptions to this, but we’ll look at those exceptions in a future tutorial on the ictus and the application of arsis and thesis. I will say here that when a note is doubled, it is often the start of a rhythmic unit and would not usually be softer than the preceding note (unless coming to the end of a phrase). Care should be made not to overdo the dynamic contrast, as the change should not be sudden or taken out of the context of the overall melody. That said, emphasizing the weak notes of a neum should (under most circumstances) be avoided.

Neum Identification

Let’s take a look again at the example chant we have used in the previous tutorials. Can you identify some of the neums that are used in this piece?

This example has some compound neums, but we see the punctum right off the bat. Ignoring the isolated punctum for the moment, we then see the torculus followed by what appears to be a variation on a pressus. After the intonation, we have a podatus with the top note doubled, another podatus with horizontal episema, followed by the climacus (observe the descending diamond notes) and a podatus apposed to a clivis, bringing us to the end of the word “timet”.

We then see the porrectus (technically a torculus resupinus although with its sweeping stroke, it can be simpler to call it a variation on the porrectus). A true porrectus occurs on the next line thrice in “mandatis”. Following this is another podatus. At “num” of “Dominum” we have a significant compound neum. As I see it, this is a two-note strophicus (distropha) followed by a torculus, followed by two clivis. Next comes a pressus and two clivis apposed to one another. We see our friend the salicus in “in mandatis” followed by some excellent examples of the porrectus.

I’ll conclude the discussion at that and leave you to practice finding neums through the remainder of the chant. For some interesting reading about the history of neums and their interpretation (there are several schools of thought), see this Wikipedia article.

Next Part in the Series

Gregorian Chant: The Ictus, Arsis, and Thesis